The Affluent Society

by

John Kenneth Galbraith

The Affluent Society

by

John Kenneth Galbraith

A book on the ways that our "convential wisdom" on economics don't track

to a wealthy society. Makes good points in favour of government spending

that convinced my small-gov peabrain. Not as inspiring of a writer as

Henry George though. Most of Galbraith's urged adjustments to our

collective feelings about taxation and gov't spending are still undone. As

relevant today as when it was written.

I do think there are

some compelling counterpoints to Galbraith's criticism of private goods

production. He often uses car manufacture as examples. He points out that

the R&D put into new car models is goaled around what can be

advertised to consumers to make them ditch their old models. I'm no fan of

car companies so I'll give him that one. But, the computer and software

revolution feels to me like a case where private companies have

substantially improved the lives of the average person. The fundamental

ground work for the internet, and computers, was laid by military research

of course, but the private market used that kernel (heh) of research and

infrastructure and fundamentally changed the world. Now, some people may

argue it hasn't been for the better. We can agree to disagree.

Anyway

in general I agree that we could do well to spend more money on public

infrastructure. Now, exactly what infrastructure that should be is the

tricky part. He makes a few to many favourable mentions of urban renewal

projects and highway building for my liking...

Out of Africa

by

Isak Dinesen

Out of Africa

by

Isak Dinesen The Mennonites of St. Jacobs and Elmira: Understanding the Variety

by

Barbara Draper

The Mennonites of St. Jacobs and Elmira: Understanding the Variety

by

Barbara Draper Scaramouche

by

Rafael Sabatini

Scaramouche

by

Rafael Sabatini

Anxious People

by

Fredrik Backman

Anxious People

by

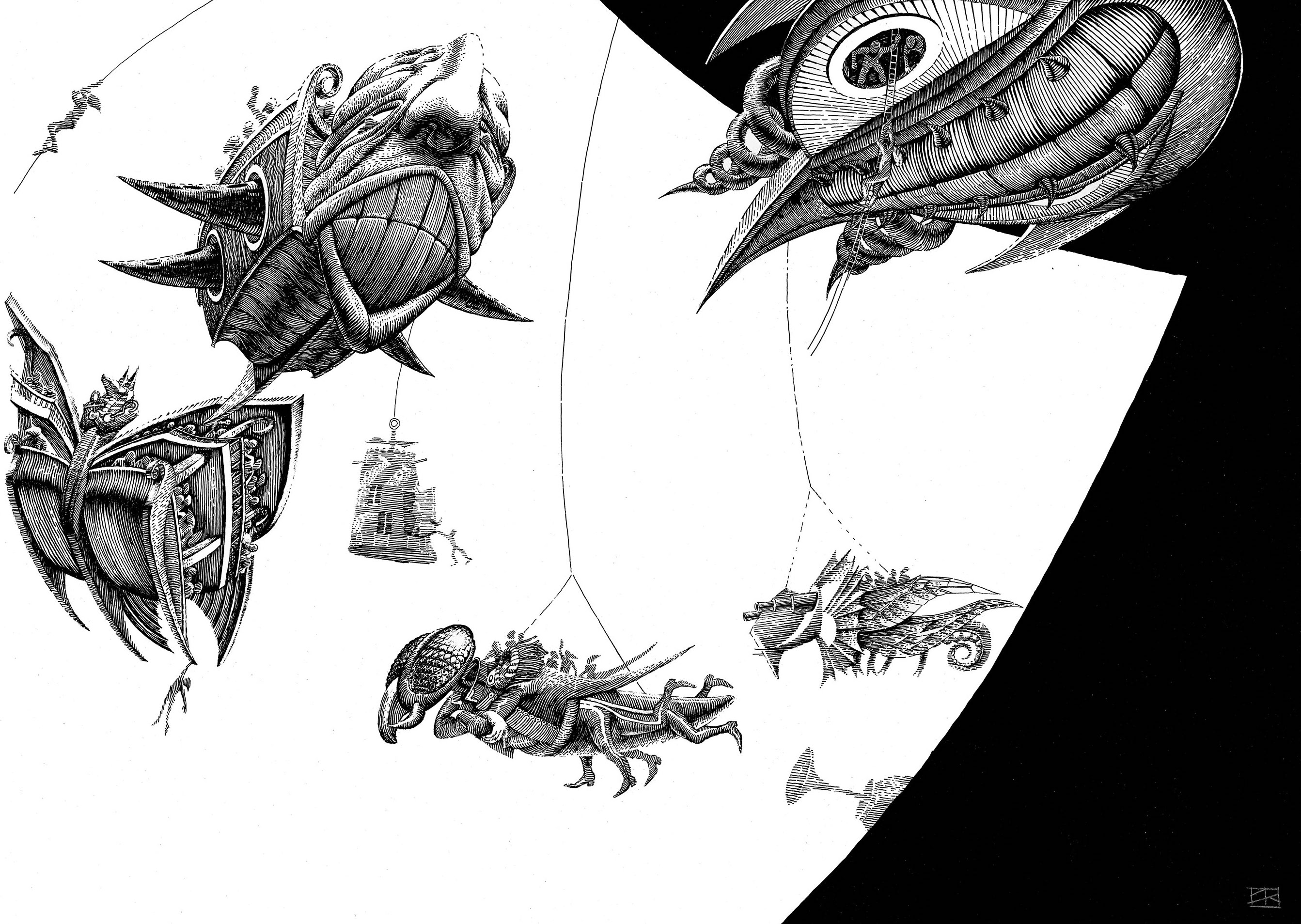

Fredrik Backman The Shadow of the Torturer

by

Gene Wolfe

The Shadow of the Torturer

by

Gene Wolfe The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas

by

Ursula K. Le Guin

The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas

by

Ursula K. Le Guin