Music is Dead; Long Live Music

November 28, 2022

It’s all folk music now.

The importance of musical movements and the innovation of new genres has been declining for some time now. I know that people have been saying this forever. I also realize that, at 26, I’m the prime age to join the “music is dead” camp; the bands I loved as a teenager are old now. But, in my mind at least, it’s not that I’m disappointed by the new styles of music coming out; I’m not even claiming that new music is particularly bad. I’m really asking: where is the new music? Not that there aren’t a billion songs being made every second, but where are the new styles? Where are the sounds that will define the early 2020s in popular culture? Listen to the first 30 seconds of this song:

Someone who is familiar with popular music of the last 50 years or so will probably be able to place this song in a timeline of musical movements with a decent amount of accuracy – i.e. they would be able to guess that the song was released in the 1980s. Will we be able to identify 2020s music the same way?

Some Armchair History

Here’s my extremely reductive layman’s theory of modern music: movements in popular music have been mostly spurred by technological and social change. Invention of instruments like the piano, the saxophone, and later the electric guitar and synthesizer pushed music forward and allowed the creation of new genres. The invention of these instruments created completely new sonic frontiers; musical landscapes which literally could not have been explored before. Before the synth was created – less than 100 years ago – synthy sounds had never existed for the entirety of human history. Of course, we are used to the miracles our age.

The 20th century was a hot time for innovation and social upheaval (probably not a coincidence). Capitalism and industrialization acted like a pair of bellows, heating society up into a more malleable and energetic state. In the US, new instruments like the electric guitar went with new social attitudes like lightning and thunder. We got jazz and rock and roll out of this. Then we got a whole bunch of other genres. New technology and artistic experimentation were supercharged by the financial incentive to create music created by the ability to record and sell records on vinyl. The result was an exponential explosion. The rate of change and diversification accelerated: it was much faster in the 1970s than in the 1930s. There were simply more people trying to make it in the music industry.

Music genres became attached to (and spawned) social scenes. These social scenes were an extremely important part of teenagers’ identities in the late 20th C. In the 1950s, youth culture itself was a novelty; the idea that teenagers represented their own identity and demographic – with their own preferences for music and movies – was new. The 1950s youth culture of Elvis, Buddy Holly and early rock-n-roll fragmented into a million subcultures: surf rock, psychedelic rock, hard rock, punk, heavy metal, disco, whatever the Talking Heads were, etc. There were movements and countermovements. People used to dress like the bands they listened to, form their politics, and hang out with other people based on music taste! That’s mostly over now. Most people my age and younger listen to “a bit of everything”. Music discovery happens through Spotify playlists and Tik Tok, where specific artists have become commoditized, accessed through playlists or videos seeking a certain sonic mood. None of this means that music is any less enjoyable to listen to, of course. For those of us who love music, it’s more accessible than ever. It’s just not socially or politically important. Again, this is a long-term trend, something that I’m sure began even before Limewire and Napster.

The End of Music

I want to be bold here and claim that music innovation has basically run it’s course, at least for now. Let me explain.

I’ve described how music innovation has generally happened along two axes: technological and social innovation. Barring some kind of miracle, I think I can confidently say that we’ve reached the end of technological innovation for sound creation. Modern synthesizers can create any tone or sound at high fidelity. Sure, new organic instruments could be created, but I think it would be hard to create something that is both (a) radically different than what already exists and (b) sounds pleasant. Artists have been experimenting with sound for a century now (actually since the beginning of time, but in the context of the modern music industry). Bryan Wilson was using bike horns and coke cans in Pet Sounds in the 1960s. The Beatles famously experimented with the sitar. I’m happy to be proven wrong, but I just don’t think that there are whole new sounds to be discovered; micro-innovations sure, but we’re never getting a new electric guitar.

That leaves social change. I think it’s hard sometimes to understand just how different the past was from today. Before teen culture came into existence in the post-WW2 years in the USA, music was not an identity for young people. The massive social change in the 50s and 60s ushered in the modern era of popular music, and the establishment of music as a foundation of identity for young people. The type of music that becomes popular acts as a mirror held up to our collective consciousness. The post-WW2 shift of our social priorities towards individualism, sexual freedom, and the pursuit of self-actualization shows up in rock n’ roll, and the popular music that came after it. If the rock n’ roll revolution was a break from what came before it, a rebellion, then the decades that have followed have been iterations on the same ideas, even as genres devour one another and fashions change like the wind. Until our culture experiences another “break” – a social paradigm shift – I don’t think we will see radical new ideas in lyrical themes or song structures (in pop music).

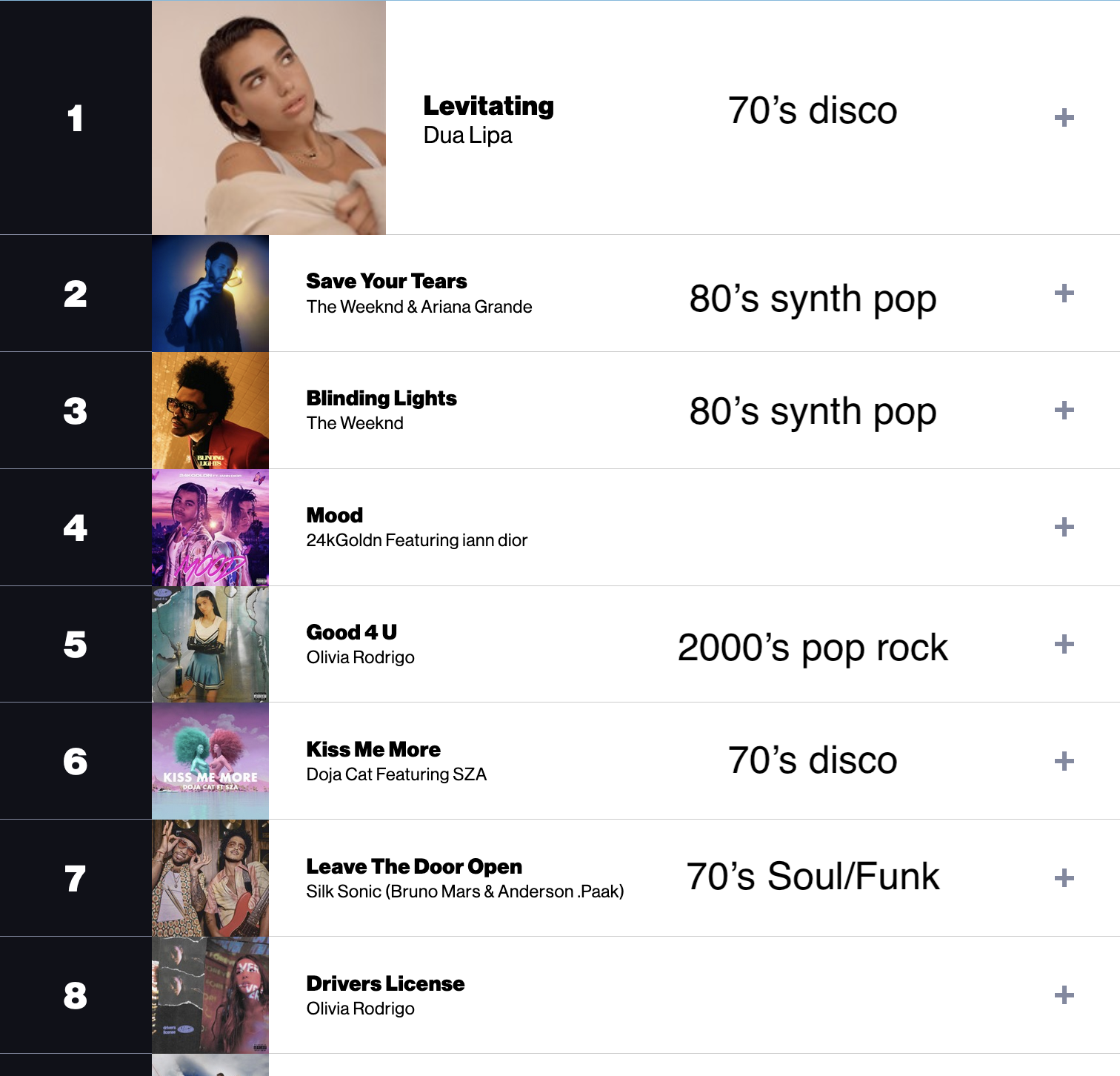

Now, this is all just my crackpot speculating. To be honest I never thought too much about this stuff before. I don’t worry about where my music comes from, I just consume. But when I go out now, the music is a hodgepodge of popular music from the last 20 years. What are the kids listening to these days? The silence is deafening. Commercially, old music now outsells new music. Personally, I can’t name any important developments or new styles of music from the last couple of years. The most recent I can think of is the late-2010s mumble rap & trap wave. But why speculate? After all, we have data on our side. Take a look at this list of the top songs of 2021. I’ve added the musical styles that I can detect as major influences on each song.

Six out of eight of the most popular songs of 2021 had major influences from legacy music genres!

Ok, ok, I understand that the pop charts aren’t exactly the best place to find the cutting edge of music. The pop charts are not for music lovers; they’re for dentist’s offices and college move-in days. There are still many, many people who love music. What are they listening to?

I’ve been listening to a brand called Drugdealer lately. I had it recommended to me by a friend who loves music, then again by another friend who loves music. I finally gave them a chance, and I like them a lot. I’ve been listening to their new album on repeat. But here’s the thing: their music wouldn’t be out of place in the 1970s. In fact, it would be impossible for almost anyone to listen to this band and not think something like “This band has a 70s sound.” Now, Drugdealer writes original songs, but sonically they fit squarely in a musical movement that came and went a long time ago. I find that a lot of the new music I enjoy is like this: new, but old.

What's Old is New

Before the industrial revolution, before capitalism kick-started an insatiable incentive system for innovating new sounds in music (and recording those sounds, and the creation of “intellectual property”), music looked a lot different. You might say that where music creation looked most similar to today was in the upper-class of Western society. There, classical music was composed by writers who were well known and paid for their work. Music was written in notation, allowing it to persist relatively unchanged (though until recording was invented it still needed musicians to be heard). Classic music composition followed movements; composers were influenced by the composers who came before them. They studied their work, improved on it, or rejected it and created something new.

For the vast majority of people, in the West and elsewhere, this was not the case. Music was passed down in living rooms, bars, at funerals and in battlefields. Music, what we now call folk music, belonged to cultures, not individuals, not specific generations. Sounds were passed on and persisted for a long time. They changed too, through evolution. Each musician leaves a fingerprint on what they play. But innovation and artistic differentiation played second fiddle to familiarity. What was appealing was more important than what was new.

We’ve gotten used to a state of affairs that is in actuality an aberration in the larger context of music history. The past 100 or so years have seen an exponential growth in music recording, innovation, technology and development. We’ve come to accept this as completely normal, but maybe we’re now in the twilight of a completely exceptional era of human history. What’s old is new. We are going back to the days of folk music. Not that everyone is going to pick up acoustic instruments again (though we did that in the 2010s), but in the broader sense of the word meaning music from tradition

Of course, much has changed. The mountain of music recorded by our ancestors still exists. It’s likely that people will still listen to the Beatles (and maybe even Blink 182) in 100, 200 years. Our great-great grandchildren will have a favourite album of the 1970s, just like myself and people my age. New music will be recorded, but popular taste will put less emphasis on what is new and instead refocus on simply what sounds nice.

Is this a bad thing? I don’t know. The human art form called music blossomed in an unexpected and beautiful way in the last century. The products of this – the recordings and the musical styles – are precious to me, personally, and billions of other people. To imagine a future where this time period is seen as a kind of “renaissance” era that came and went in a few generations is sad to me in some way. Still, I welcome the “folkification” of music. I want to enjoy music simply for the joy it gives me, rather than being concerned about listening to the right genres and the right artists. When all the hype is over, when the glamour and lifestyle is stripped away, what we’re left with is what we really came for anyways.

P.S.

The fate that's come for the music industry is nothing new either, after all. It has quietly happened to every individual music scene whose moment in the spotlight is over. Mark Knopfler of Dire Straits understood this. In the 70s he walked into a bar in south London and heard a band playing swing music. The place wasn't crowded; most people there weren't even paying attention. The players worked day jobs. You've probably been in a scene like that before. It's not too surprising; swing was popular in the 30s, by the 70s it wasn't cool anymore. Mark wrote a song about that experience, one of my favourites ever, "Sultans of Swing". It's an ode, not to famous artists or rock stars, but to masters nonetheless.

Well now you step inside but you don't see too many faces

Coming in out of the rain they hear the jazz go down

Competition in other places

Uh but the horns they blowin' that sound

…

You check out guitar George, he knows-all the chords

Mind, it's strictly rhythm he doesn't want to make it cry or sing

They said an old guitar is all, he can afford

When he gets up under the lights to play his thing

And Harry doesn't mind, if he doesn't, make the scene

He's got a daytime job, he's doing alright

He can play the Honky Tonk like anything

Savin' it up, for Friday night